Dickens and America: An Uneasy Relationship

Charles Dickens was the product of a modest upbringing in 19th century England. He retained vivid images of a fondly remembered childhood, but those happier times were interrupted when his father John, who struggled beyond his means to provide for his family, was sent to a debtor's prison. His wife and youngest children would accompany him, as was the custom. But Charles, only twelve at the time, was considered an economic asset to the family and sent to a shoe-polish factory where he would toil away with other underprivileged members of society. This would come to shape his views of the working class, strongly influencing his work in later years, and contributing to his interest in America, a hopeful young nation that was described as a haven for the oppressed.

Dickens in America

Dickens, already the most celebrated writer in his own country, was just shy of thirty years old when he decided to make the voyage to America in order that he might tour the country and discover for himself whether his optimism in the newly formed democratic nation was justified. He was already very well known for his wildly popular works The Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist and had just completed his fifth novel Barnaby Rudge. He set sail from Liverpool on the third of January in 1842. With him aboard the steamship Britannia was his wife Catherine, and her maid Anne Brown. It was a rough start to a journey, the seas reportedly being the stormiest they had been in years. He wrote that his attempts to comfort his traveling companions with hot brandy and water were particularly difficult, as the couch they were seated upon shifted back and forth with the tumultuous sea, and the glass was all but empty by the time he caught them. He felt that his quarters were also unsuitably small, writing that their luggage could "no more be got in at the door, not to say stowed away, than a giraffe could be forced into a flowerpot." But his spirits were heightened upon his arrival in Boston, January 22, where he was immediately greeted with an unprecedented reverence and enthusiasm.

Dickens remained in Boston for nearly two weeks. From there he traveled for some time around New England, eventually ending up in New York City. He was treated grandly by the elite members of New York society who organized a lavish event at the city's most celebrated venue, the Park Theatre, which was decorated with wreaths, paintings, and even a bust of Dickens himself accompanied by a soaring eagle, all in honor of their distinguished visitor. Thousands of people attended and Dickens and Catherine danced the night away, reveling in the unique experience. At a dinner the following night he said that if he were to grow old "the scenes of this and other evenings will shine as brightly to my dull eyes 50 years hence as now". But the unbridled enthusiasm and admiration from the American people that fostered Dickens' initial feelings of exuberance would soon become overwhelming. And the seed of resentment was thus planted, slowly watered over the remainder of his travels, culminating in a conflict of interest between Dickens and the American people and ill will that would color their relationship.

America perhaps loved Dickens too much. His celebrity soon became a hindrance, rather than something by which he felt honored and appreciated. One instance that was particularly unsettling for him occurred while their boat was docked in Cleveland. He awoke to find that a group of men were gathered outside of his cabin window, looking in on he and his wife as they slept. Much like modern stars of music, film, and television, Dickens was restricted in his every activity. He was unable to move freely about the country without his every move being scrutinized by the overzealous public. "If I turn into the street, I am followed by a multitude," he wrote in a letter. There was a distinct lack of the social graces he was accustomed to in England as well. The various people who he routinely shared meals with throughout his trip he generally saw as vulgar, offensive animals. The prevalent use of chewing tobacco left an especially uneasy impression on him. He was disgusted by the habit and saw men spitting out "tobacco-tinctured saliva" everywhere he went, including the White House where he met President John Tyler.

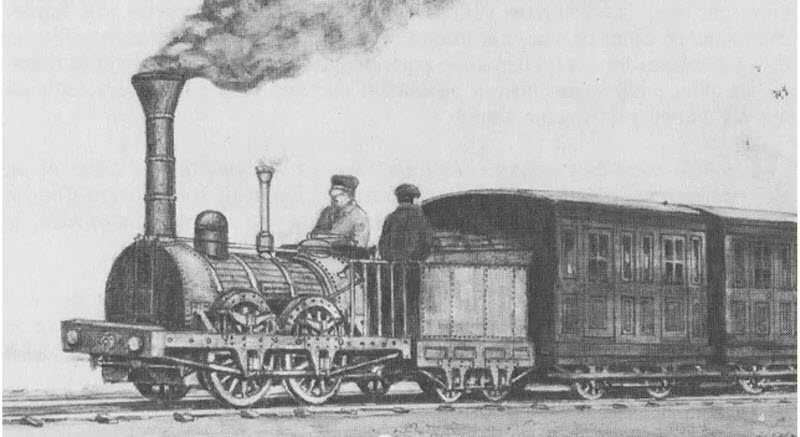

A Scene From American Notes, Based on Dickens Travels in North America

There were also other, less trivial matters that disappointed him about his visit to Washington. He came away with a less than favorable view of the American politics he was once so optimistic about. In American Notes, written upon his return to England, he described what he saw as "Despicable trickery at elections; under-handed tamperings with public officers; and cowardly attacks upon opponents, with scurrilous newspapers for shields, and hired pens for daggers." He felt that Americans were less concerned with ideals than they were with money. He was disenchanted by slavery in America, something he saw as greatly hypocritical. His hopes for a more enlightened society were greatly diminished. "This is not the republic of my imagination," he wrote home.

The greatest rift of all between Dickens and the American people occurred as the result of a matter to which our current generations are intimately acquainted. Much of Dickens' popularity in America came from the pirating of his works. There was no international copyright law at the time, allowing American publishers to take advantage, generally without the least bit compensation. Dickens argued the case throughout his tour. His goals, although generally perceived to be self-motivated by the American people, were not entirely so. He argued that the lack of copyright laws was a disservice to American writers, their novels costing more than half the price of one of his pirated works and therefore being vastly outsold. The public, urged on by the press who greatly depended on freely printing his serials, reacted negatively towards his pleas for fairness. Both Dickens and the people were left with the perception that the other was driven by greed.

Upon his return home, Dickens, left embittered by his experiences and shocked by the culture, penned American Notes, an unforgiving account of his travels. He followed that with his next novel, Martin Chuzzlewit, in which he sends his main character to America, the fictional visit becoming a vehicle for Dickens to release some of his anger through scathing satire. The press and the people, of course, looked upon these writings highly unfavorably, considering them to be libelous. Many of the writers Dickens had met, who had been supportive of his campaign for spreading the message of copyright law, were also outraged and felt betrayed by his actions. A man who was once welcomed as a hero, now seemed like a traitor, and for a time his popularity waned. Some scholars maintain that Dickens' visit to America also marked a turning point in his writing, which became less hopeful concerning human nature in works such as David Copperfield and Bleak House.

As time passed, Dickens' popularity once again rose, even in the land he had scorned. After less success than he had hoped for amongst his British audience with Martin Chuzzlewit, he decided he would write what would perhaps become his most celebrated work, A Christmas Carol. He began to perform public readings of this and other works that proved to be wildly successful, with Britons lining the streets for tickets. Eventually, with the bad blood fading, Dickens sent scouts to gauge interest in America for a possible return. All the reports came back favorably and despite his declining health and urges by some of his closest friends not to undertake the voyage, he arrived again in Boston in late November 1867. Once again he was welcomed with adoration, and stories in the press featuring the negative aspects of his previous visit gained little traction. Despite his ailments he refused to cancel a single show. The audiences hung on his every word, and almost all of his critics were won over. Over the course of five months and seventy-six performances he had profited a total of £19,000. A dinner was held in his honor in New York in April of 1868 where he remarked on the changes America, and he himself, had gone through since his last trip. He was so moved by his reception that he vowed to include an appendix to both works that were critical of America, noting the favorable conditions he had found. And with that, the grudge was dead.