Biography of Charles Dickens by His Daughter Mamie

Prev

| Next

| Contents

CHAPTER VI.

Last words spoken in public.--A railroad accident in 1865.--At home after

his American visit.--"Improvements" at "Gad's Hill."--At "Gad's Hill"

once more.--The closing days of his life.--Burial at Westminster.

My father gave his last reading in St. James' Hall, London, on the

fifteenth of March. The programme included "The Christmas Carol" and the

"Trial" from "Pickwick." The hall was packed by an enormous audience,

and he was greeted with all the warmth which the personal affection felt

for the reader inspired. We all felt very anxious for him, fearing that

the excitement and emotion which must attend upon his public farewell

would have a bad effect upon him. But it had no immediate result, at any

rate, much to our relief.

I do not think that my father ever--and this is saying a great

deal--looked handsomer nor read with more ability than on this, his last

appearance. Mr. Forster writes: "The charm of his reading was at its

height when he shut the volume of 'Pickwick' and spoke in his own person.

He said that for fifteen years he had been reading his own books to

audiences whose sensitive and kindly recognition of them had given him

instruction and enjoyment in his art such as few men could have had; but

that he nevertheless thought it well now to retire upon older

associations, and in future to devote himself exclusively to the calling

which first made him known. 'In but two short weeks from this time I

hope that you may enter in your own homes on a new series of readings, at

which my assistance will be indispensable; but from these garish lights I

vanish now, for evermore, with a heartfelt, grateful, respectful,

affectionate farewell.'"

There was a dead silence as my father turned away, much moved; and then

came from the audience such a burst and tumult of cheers and applause as

were almost too much to bear, mixed as they were with personal love and

affection for the man before them. He returned with us all to "Gad's

Hill," very happy and hopeful, under the temporary improvement which the

rest and peace of his home brought him, and he settled down to his new

book, "Edwin Drood," with increased pleasure and interest.

His last public appearances were in April. On the fifth he took the

chair at the News-venders' dinner. On the thirtieth he returned thanks

for "Literature" at the Royal Academy banquet. In this speech he alluded

to the death of his old friend, Mr. Daniel Maclise, winding up thus: "No

artist, of whatsoever denomination, I make bold to say, ever went to his

rest leaving a golden memory more pure from dross, or having devoted

himself with a truer chivalry to the art-goddess whom he worshipped."

These words, with the old, true, affectionate ring in them, were the last

spoken by my father in public.

About 1865 my dear father's health began to give way, a peculiar

affection of the foot which frequently caused him the greatest agony and

suffering, appearing about this time. Its real cause--overwork--was not

suspected either by his physicians or himself, his vitality seeming

something which could not wear out; but, although he was so active and

full of energy, he was never really strong, and found soon that he must

take more in the way of genuine recreation. He wrote me from France

about this time: "Before I went away I had certainly worked myself into a

damaged state. But the moment I got away I began, thank God, to get

well. I hope to profit from this experience, and to make future dashes

from my desk before I need them."

It was while on his way home after this trip that he was in the terrible

railroad accident to which he afterwards referred in a letter to a

friend, saying, that his heart had never been in good condition after

that accident. It occurred on the ninth of June, a date which five years

later was the day of his death.

He wrote describing his experiences: "I was in the only carriage which

did not go over into the stream. It was caught upon the turn by some of

the ruin of the bridge, and became suspended and balanced in an

apparently impossible manner. Two ladies were my fellow-passengers, an

old one and a young one. This is exactly what passed--you may judge from

it the length of our suspense: Suddenly we were off the rail and beating

the ground as the car of a half-emptied balloon might. The old lady

cried out 'My God!' and the young one screamed. I caught hold of them

both (the old lady sat opposite, and the young one on my left) and said:

'We can't help ourselves, but we can be quiet and composed. Pray, don't

cry out!' The old lady immediately answered: 'Thank you, rely upon me.

Upon my soul I will be quiet.' We were then all tilted down together in

a corner of the carriage, which then stopped. I said to them thereupon:

'You may be sure nothing worse can happen; our danger must be over. Will

you remain here without stirring while I get out of the window?' They

both answered quite collectedly 'Yes,' and I got out without the least

notion of what had happened. Fortunately I got out with great caution,

and stood upon the step. Looking down I saw the bridge gone, and nothing

below me but the line of rail. Some people in the other two compartments

were madly trying to plunge out at a window, and had no idea that there

was an open, swampy field fifteen feet down below them, and nothing else.

The two guards (one with his face cut) were running up and down on the

down-track of the bridge (which was not torn up) quite wildly. I called

out to them: 'Look at me! Do stop an instant and look at me, and tell me

whether you don't know me?' One of them answered: 'We know you very

well, Mr. Dickens.' 'Then,' I said, 'my good fellow, for God's sake,

give me your key, and send one of those laborers here, and I'll empty

this carriage.' We did it quite safely, by means of a plank or two, and

when it was done I saw all the rest of the train, except the two baggage

vans, down the stream. I got into the carriage again for my brandy

flask, took off my travelling hat for a basin, climbed down the

brickwork, and filled my hat with water. Suddenly I came upon a

staggering man, covered with blood (I think he must have been flung clean

out of his carriage), with such a frightful cut across the skull that I

couldn't bear to look at him. I poured some water over his face, and

gave him some to drink, then gave him some brandy, and laid him down on

the grass.

He said 'I am gone,' and died afterwards. Then I stumbled over a lady

lying on her back against a little pollard tree, with the blood streaming

over her face (which was lead color) in a number of distinct little

streams from the head. I asked her if she could swallow a little brandy,

and she just nodded, and I gave her some and left her for somebody else.

The next time I passed her she was dead. Then a man examined at the

inquest yesterday (who evidently had not the least remembrance of what

really passed) came running up to me and implored me to help him find his

wife, who was afterward found dead. No imagination can conceive the ruin

of the carriages, or the extraordinary weights under which the people

were lying, or the complications into which they were twisted up among

iron and wood, and mud and water. I am keeping very quiet here."

This letter was written from "Gad's Hill" four days after the accident.

We were spared any anxiety about our father, as we did not hear of the

accident until after we were with him in London. With his usual care and

thoughtfulness he had telegraphed to his friend Mr. Wills, to summon us

to town to meet him. The letter continues: "I have, I don't know what to

call it, constitutional (I suppose) presence of mind, and was not the

least fluttered at the time. I instantly remembered that I had the MS.

of a number with me, and clambered back into the carriage for it. But in

writing these scanty words of recollection I feel the shake, and am

obliged to stop."

We heard, afterwards, how helpful he had been at the time, ministering to

the dying! How calmly and tenderly he cared for the suffering ones about

him!

But he never recovered entirely from the shock. More than a year later

he writes: "It is remarkable that my watch (a special chronometer) has

never gone quite correctly since, and to this day there sometimes comes

over me, on a railway and in a hansom-cab, or any sort of conveyance, for

a few seconds, a vague sense of dread that I have no power to check. It

comes and passes, but I cannot prevent its coming."

I have often seen this dread come upon him, and on one occasion, which I

especially recall, while we were on our way from London to our little

country station "Higham," where the carriage was to meet us, my father

suddenly clutched the arms of the railway carriage seat, while his face

grew ashy pale, and great drops of perspiration stood upon his forehead,

and though he tried hard to master the dread, it was so strong that he

had to leave the train at the next station. The accident had left its

impression upon the memory, and it was destined never to be effaced. The

hours spent upon railroads were thereafter often hours of pain to him. I

realized this often while travelling with him, and no amount of assurance

could dispel the feeling.

Early in May of 1868, we had him safely back with us, greatly

strengthened and invigorated by his ocean journey home, and I think he

was never happier at "Gad's Hill" than during his last two years there.

During that time he had a succession of guests, and none were more

honored, nor more heartily welcomed, than his American friends. The

first of these to come, if I remember rightly, was Mr. Longfellow, with

his daughters. My father writes describing a picnic which he gave them;

"I turned out a couple of postilions in the old red jacket of the old

Royal red for our ride, and it was like a holiday ride in England fifty

years ago. Of course we went to look at the old houses in Rochester, and

the old Cathedral, and the old castle, and the house for the six poor

travellers.

"Nothing can surpass the respect paid to Longfellow here, from the Queen

downward. He is everywhere received and courted, and finds the working

men at least as well acquainted with his books as the classes socially

above them."

Between the comings and goings of visitors there were delightfully quiet

evenings at home, spent during the summer in our lovely porch, or walking

about the garden, until "tray time," ten o'clock. When the cooler nights

came we had music in the drawing-room, and it is my happiness now to

remember on how many evenings I played and sang all his favorite songs

and tunes to my father during these last winters while he would listen

while he smoked or read, or, in his more usual fashion, paced up and down

the room. I never saw him more peacefully contented than at these times.

There were always "improvements"--as my father used to call his

alterations--being made at "Gad's Hill," and each improvement was

supposed to be the last. As each was completed, my sister--who was

always a constant visitor, and an exceptionally dear one to my

father--would have to come down and inspect, and as each was displayed,

my father would say to her most solemnly: "Now, Katie, you behold your

parent's latest and last achievement." These "last improvements" became

quite a joke between them. I remember so well, on one such occasion,

after the walls and doors of the drawing-room had been lined with

mirrors, my sister's laughing speech to "the master": "I believe papa,

that when you become an angel your wings will be made of looking-glass

and your crown of scarlet geraniums."

And here I would like to correct an error concerning myself. I have been

spoken of as my father's "favorite daughter." If he had a favorite

daughter--and I hope and believe that the one was as dear to him as the

other--my dear sister must claim that honor. I say this ungrudgingly,

for during those last two years my father and I seemed to become more

closely united, and I know how deep was the affectionate intimacy at the

time of his death.

The "last improvement"--in truth, the very last--was the building of a

conservatory between the drawing and dining rooms. My father was more

delighted with this than with any previous alteration, and it was

certainly a pretty addition to the quaint old villa. The chalet, too,

which he used in summer as his study, was another favorite spot at his

favorite "Gad's Hill."

In the early months of 1870 we moved up to London, as my father had

decided to give twelve farewell readings there. He had the sanction of

the late Sir Thomas Watson to this undertaking, on condition that there

should be no railway journeys in connection with them. While we were in

London he made many private engagements, principally, I know, on my

account, as I was to be presented that spring.

During this last visit to London, my father was not, however, in his

usual health, and was so quickly and easily tired that a great number of

our engagements had to be cancelled. He dined out very seldom, and I

remember that on the last occasion he attended a very large dinner party

the effort was too much for him, and before the gentlemen returned to the

drawing-room, he sent me a message begging me to come to him at once,

saying that he was in too great pain to mount the stairs. No one who had

watched him throughout the dinner, seeing his bright, animated face, and

listening to his cheery conversation, could have imagined him to be

suffering acute pain.

He was at "Gad's Hill" again by the thirtieth of May, and soon hard at

work upon "Edwin Drood." Although happy and contented, there was an

appearance of fatigue and weariness about him very unlike his usual air

of fresh activity. He was out with the dogs for the last time on the

afternoon of the sixth of June, when he walked into Rochester for the

"Daily Mail." My sister, who had come to see the latest "improvement,"

was visiting us, and was to take me with her to London on her return, for

a short visit. The conservatory--the "improvement" which Katie had been

summoned to inspect--had been stocked, and by this time many of the

plants were in full blossom. Everything was at its brightest and I

remember distinctly my father's pleasure in showing my sister the

beauties of his "improvement."

We had been having most lovely weather, and in consequence, the outdoor

plants were wonderfully forward in their bloom, my father's favorite red

geraniums making a blaze of color in the front garden. The syringa

shrubs filled the evening air with sweetest fragrance as we sat in the

porch and walked about the garden on this last Sunday of our dear

father's life. My aunt and I retired early and my dear sister sat for a

long while with my father while he spoke to her most earnestly of his

affairs.

As I have already said my father had such an intense dislike for

leave-taking that he always, when it was possible, shirked a farewell,

and we children, knowing this dislike, used only to wave our hands or

give him a silent kiss when parting. But on this Monday morning, the

seventh, just as we were about to start for London, my sister suddenly

said: "I must say good-bye to papa," and hurried over to the chalet

where he was busily writing. As a rule when he was so occupied, my

father would hold up his cheek to be kissed, but this day he took my

sister in his arms saying: "God bless you, Katie," and there, "among the

branches of the trees, among the birds and butterflies and the scent of

flowers," she left him, never to look into his eyes again.

In the afternoon, feeling fatigued, and not inclined to much walking, he

drove with my aunt into Cobham. There he left the carriage and walked

home through the park. After dinner he remained seated in the

dining-room, through the evening, as from that room he could see the

effect of some lighted Chinese lanterns, which he had hung in the

conservatory during the day, and talked to my aunt about his great love

for "Gad's Hill," his wish that his name might become more associated

with the place, and his desire to be buried near it.

On the morning of the eighth he was in excellent spirits, speaking of his

book, at which he intended working through the day and in which he was

most intensely interested. He spent a busy morning in the chalet, and it

must have been then that he wrote that description of Rochester, which

touched our hearts when we read it for the first time after its writer

lay dead: "Brilliant morning shines on the old city. Its antiquities and

ruins are surpassingly beautiful with the lusty ivy gleaming in the sun

and the rich trees waving in the balmy air. Changes of glorious light

from moving boughs, songs of birds, scents from gardens, woods and

fields, or rather, from the one great garden of the whole cultivated

island in its yielding time, penetrate into the cathedral, subdue its

earthly odor, and preach the Resurrection and the Life."

He returned to the house for luncheon, seemingly perfectly well and

exceedingly cheerful and hopeful. He smoked a cigar in his beloved

conservatory, and went back to the chalet. When he came again to the

house, about an hour before the time fixed for an early dinner, he was

tired, silent and abstracted, but as this was a mood very usual to him

after a day of engrossing work, it caused no alarm nor surprise to my

aunt, who happened to be the only member of the family at home. While

awaiting dinner he wrote some letters in the library and arranged some

trifling business matters, with a view to his departure for London the

following morning.

* * * * *

It was not until they were seated at the dinner-table that a striking

change in the color and expression of his face startled my aunt. Upon

her asking him if he were ill, he answered "Yes, very ill; I have been

very ill for the last hour." But when she said that she would send for a

physician he stopped her, saying that he would go on with dinner, and

afterward to London.

He made an earnest effort to struggle against the seizure which was fast

coming over him, and continued to talk, but incoherently and very

indistinctly. It being now evident that he was in a serious condition,

my aunt begged him to go to his room before she sent for medical aid.

"Come and lie down," she entreated. "Yes, on the ground," he answered

indistinctly. These were the last words that he uttered. As he spoke,

he fell to the floor. A couch was brought into the dining-room, on which

he was laid, a messenger was dispatched for the local physician,

telegrams were sent to all of us and to Mr. Beard. This was at a few

minutes after six o'clock. I was dining at a house some little distance

from my sister's home. Dinner was half over when I received a message

that she wished to speak to me. I found her in the hall with a change of

dress for me and a cab in waiting. Quickly I changed my gown, and we

began the short journey which brought us to our so sadly-altered home.

Our dear aunt was waiting for us at the open door, and when I saw her

face I think the last faint hope died within me.

All through the night we watched him--my sister on one side of the couch,

my aunt on the other, and I keeping hot bricks to the feet which nothing

could warm, hoping and praying that he might open his eyes and look at

us, and know us once again. But he never moved, never opened his eyes,

never showed a sign of consciousness through all the long night. On the

afternoon of the ninth the celebrated London physician, Dr. Russell

Reynolds, (recently deceased), was summoned to a consultation by the two

medical men in attendance, but he could only confirm their hopeless

verdict. Later, in the evening of this day, at ten minutes past six, we

saw a shudder pass over our dear father, he heaved a deep sigh, a large

tear rolled down his face and at that instant his spirit left us. As we

saw the dark shadow pass from his face, leaving it so calm and beautiful

in the peace and majesty of death, I think there was not one of us who

would have wished, could we have had the power, to recall his spirit to

earth.

* * * * *

I made it my duty to guard the beloved body as long as it was left to us.

The room in which my dear father reposed for the last time was bright

with the beautiful fresh flowers which were so abundant at this time of

the year, and which our good neighbours sent to us so frequently. The

birds were singing all about and the summer sun shone brilliantly.

"And may there be no sadness of farewell

When I embark.

For though when from out our bourne of Time and Place

The flood may bear me far,

I hope to see my Pilot face to face

When I have crossed the bar.'

Those exquisite lines of Lord Tennyson's seem so appropriate to my

father, to his dread of good-byes, to his great and simple faith, that I

have ventured to quote them here.

* * * * *

On the morning after he died, we received a very kind visit from Sir John

Millais, then Mr. Millais, R.A. and Mr. Woolner, R.A. Sir John made a

beautiful pencil drawing of my father, and Mr. Woolner took a cast of his

head, from which he afterwards modelled a bust. The drawing belongs to

my sister, and is one of her greatest treasures. It is, like all Sir

John's drawings, most delicate and refined, and the likeness absolutely

faithful to what my father looked in death.

* * * * *

You remember that when he was describing the illustrations of Little

Nell's death-bed he wrote: "I want it to express the most beautiful

repose and tranquillity, and to have something of a happy look, if death

can." Surely this was what his death-bed expressed--infinite happiness

and rest.

As my father had expressed a wish to be buried in the quiet little

church-yard at Shorne, arrangements were made for the interment to take

place there. This intention was, however, abandoned, in consequence of a

request from the Dean and chapter of Rochester Cathedral that his bones

might repose there. A grave was prepared and everything arranged when it

was made known to us, through Dean Stanley, that there was a general and

very earnest desire that he should find his last resting-place in

Westminster Abbey. To such a tribute to our dear father's memory we

could make no possible objection, although it was with great regret that

we relinquished the plan to lay him in a spot so closely identified with

his life and works.

The only stipulation which was made in connection with the burial at

Westminster Abbey was that the clause in his will which read: "I

emphatically direct that I be buried in an inexpensive, unostentatious

and and strictly private manner," should be strictly adhered to, as it

was.

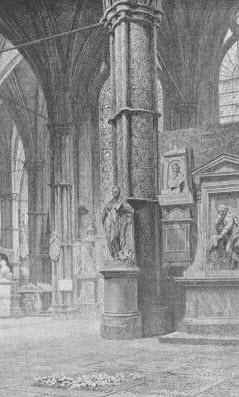

At midday on the fourteenth of June a few friends and ourselves saw our

dear one laid to rest in the grand old cathedral. Our small group in

that vast edifice seemed to make the beautiful words of our beautiful

burial service even more than usually solemn and touching. Later in the

day, and for many following days, hundreds of mourners flocked to the

open grave, and filled the deep vault with flowers. And even after it

was closed Dean Stanley wrote: "There was a constant pressure to the spot

and many flowers were strewn upon it by unknown hands, many tears shed

from unknown eyes."

[Picture: Charles Dickens' Grave]

And every year on the ninth of June and on Christmas day we find other

flowers strewn by other unknown hands on that spot so sacred to us, as to

all who knew and loved him. And every year beautiful bright-coloured

leaves are sent to us from across the Atlantic, to be placed with our own

flowers on that dear grave; and it is twenty-six years now since my

father died!

And for his epitaph what better than my father's own words:

"Of the loved, revered and honoured head, thou canst not turn one

hair to thy dread purposes, nor make one feature odious. It is not

that the hand is heavy and will fall down when released; it is not

that the heart and pulse are still; but that the hand was open,

generous and true, the heart brave, warm and tender, and the pulse a

man's. Strike! shadow, strike! and see his good deeds springing from

the wound, to sow the world with life immortal."

Footnotes:

{15} When I write about my aunt, or "Auntie," as no doubt I may often

have occasion to do, it is of the aunt par excellence, Georgina

Hogarth. She has been to me ever since I can remember anything, and to

all of us, the truest, best and dearest friend, companion and counsellor.

To quote my father's own words: "The best and truest friend man ever

had."

Prev

| Next

| Contents